Portulaca oleracea, known as Moss Rose, Common Purslane or Verdolaga, is considered a beneficial weed. Its leaves are edible, having a slightly sour and salty flavor. It was included in the genetic banks for this reason, but mostly for its use as a companion plant that stabilizes moisture in the soil, retrieves nutrients from deep in the soil layer (thus making them available to other plants), and otherwise conditions rocky and inhospitable soil for food crops such as corn. It is occasionally considered a weed due to its invasive properties. Purslane is common on Skarsia, but was never introduced to Dolparessa as the same evolutionary niche is filled by the Cu’endhari nau’gsh, which regulates soil and weather conditions. To rid a garden of purslane, the plant must be deeply smothered with mulch.

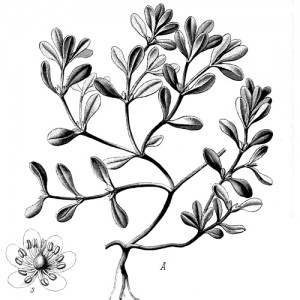

Illustration adapted from Prof. Dr. Otto Wilhelm Thomé, Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz, 1885.

It is at this point that I, Ailann Tiarnan, become involved in the story.

Well, that’s only correct in a very limited sense. I suppose it depends on how I define “I.” This is a philosophical matter left largely untouched by humans. They’ll ask “Who am I?” but not “What is I?” Cu’enashti, on the other hand, have ample reason to ponder this question, but few have bothered. They have little concern beyond the needs and pleasure of their Chosen and the elements of Cu’endhari culture which were crafted by the Cantor. Because the Cantor was a lone branch for almost a thousand years, her sense of “I” was closer to the human norm than other Cu’enashti. Conversely, the Ashtara grove has, at this writing, 54 emanated branches, each with his own personality, memories and unique physical form. The question of what constitutes an “I” concerns us greatly, and, as it turns out, is a much deeper problem than we had ever imagined.

But I (that is, Ailann Tiarnan) am getting ahead of myself yet again. For now, suffice it to say that when other emanations – Patrick, Lugh, Owen, the mothman – are physically present, I can participate in the same experience as they. In a very real sense, I am them. Their reactions, emotions, thought processes and even physical sensations are different from mine, but I can experience them first hand. At the same time, I maintain a sense of distinct identity. While the events of the last chapter were occurring, I knew I was Ailann even when I was being Owen.

But it was time for Ailann Tiarnan to manifest physically. Owen and Lugh had been the right choices for the Convocation, but during a time of trouble, the human population would want the reassuring presence of their god. As usual, it was left to me to think of the right message to inspire and comfort the people.

What was I to say? They would want to know why this terrible thing had happened. I wasn’t absolutely certain, but between Tara’s vision and some insider information we had previously gotten from a long lost relative of Tara’s named Aidenne Letreque, I had a reasonably good idea. Some of the more radical Cu’enmerengi were disgruntled with our leadership. They thought that Cu’enashti pandered to humans, that Elma’ashra, Ashpremma, Philosophia and myself were monstrous abominations because we travelled in space, that we’d forgotten our roots on Dolparessa. They didn’t believe that the K’ntasari were real nau’gsh and thought they deserved no place in the Convocation. They felt that Cu’enmerengi were more suitable to govern the affairs of the Forest.

I had considered their point-of-view carefully. I had no personal desire to impose my will upon anyone, and if it were only a matter of government, my own inclination would be to step aside in favor of an elected representation. Unfortunately, there were a number of contraindications:

- In theory, I had no power in the Convocation of the Forest to renounce. Archon of Skarsia was a human title; the powers vested in me as the Living God were accomplished by human means and recognized by human authority. In practice, the situation was much different. My influence rivalled the Cantor’s, which was part of the reason why I was a target.

- The Domha’vei was an oligarchy. Its human inhabitants would read any renunciation of authority as weakness. This would cause both political and economic instability. Furthermore, the Cu’enashti were, by desire and necessity, subservient to their human Chosen. If the humans would not accept democracy, neither would they.

- The dissidents’ hatred of the K’ntasari was pure racism; their attitude towards those of us who had made the leap into space a base fear of the unknown and unusual. They didn’t just want power out of our hands; they wanted us not to exist.

- Most importantly, I had priorities. In order to achieve Tara’s destiny, we needed to evolve. In order for Tara to evolve, humanity had to evolve with us. Circumstances had led the Domha’vei to become the locus of man’s foray into trans-galactic immortality. It was necessary for the system to be wealthy, engaged in cutting-edge research, stable and prosperous enough to dedicate significant resources and resourcefulness to this project. In short, I needed to govern, and govern well, for Tara’s sake.

After turning the options over in my mind, I concluded that it was best not to focus on the cause until I had more concrete information. I would instead assure the populace that a complete investigation would follow. A better approach was to address the immediate tragedy by eulogizing Heavensent and consoling the Cantor in her loss.

Tara had already made a brief statement and returned to Court Emmere. This was common; long ago, Lord Danak had discovered that the Matriarch was best taken in small doses. I was inspiring and dignified; she was cynical, quick-tempered and easily bored. Consequently, the task of handling the media was generally mine.

Immediately after my address, we adjourned to a reception held in a catering facility adjacent to the Capitol Building. A small group of journalists had been invited to drink my champagne, eat my caviar, and badger me for answers. Of course Bobert Crandon was there; he was the President of Vega Vids and our own personal media push director. It was his task to make me look good. But we also had to deal with the annoyingly critical and persistent Sara Howe-Dumfaller. The truth was that she was a real journalist and Crandon an extraordinary publicist. I could hardly begrudge them for doing their jobs. In any case, I had carefully prepared everything I was going to say about the horrific attack, and was confident I could stay on-message.

“Your Holiness,” said Howe-Dumfaller, “I’ve seen the footage…quite literally. So why don’t you explain what everyone wants to know – since when does a mothman have legs?”

“That’s a very personal question,” I stammered, grabbing a glass of champagne from a nearby server. Did she really think that was more important than the burning of the Cantor Tree? Maybe she did – a physical change in the form of God might be taken as some kind of portent. Or maybe she was she just trying to throw me off guard. I was certain that I was no god in her eyes – or, at least, that she had no fear of asking God impertinent questions. As my mind spun, I downed a second glass.

So perhaps I was not at my sharpest when I saw a man approaching, sensed from a distance that he was not hostile – but he was definitely keeping secrets. In ten seconds, he would brush past me, pressing a note into my hand. But in five seconds, before he could pass the message, he would be tackled by security unless I acted. I made eye contact with my escort, Captain Leukk Zosim, the head of the official palace guards, shaking my head almost imperceptibly.

The note said, “I am taking a great risk. I was part of the Cu’enmerengi resistance, but I can’t approve of what they did to the Cantor Tree. Meet me alone in front of the custodian’s room on level three, and I’ll let you in on the secret.”

Meeting him alone was going to be the difficult bit. I was usually surrounded by visible guards and invisible SSOps agents; today, security was doubled. Not to mention that the room was packed with watchful journalists. I touched Zosim on the shoulder. “Cover for me,” I whispered. “I have to, ah, talk to Mithras.”

Zosim’s expression clearly said You have got to be kidding, but what he really said was “Of course, your Holiness.” He knew better than to question the will of God.

*****

The man identified himself as a Cu’enmerengi named Jaxxon. “Just follow me,” he urged. “When you see it, you’ll understand. Trust me.” We descended to the basement level. “There are some tunnels down through here,” said Jaxxon. I didn’t tell him that I already knew. I could smell the composition of the walls, feel the direction of the air currents in the passages. Although the stale, damp air was unpleasant, I preferred it to the building above. Air filtration and processing is so thorough in developed cities that the atmosphere seems thin and flavorless. Human scents, both natural and artificial, are whisked away so quickly that it’s scarcely worth the price of perfume. A pity. I enjoy the way humans smell.

Thus, I was not disoriented in the maze-like tunnels although the circuitous route Jaxxon was taking was almost certainly devised for that purpose. At any point, I could’ve identified latitude, longitude and elevation down to eleven decimals, if need be. If I were Valentin, I probably would’ve bothered. As it was, I certainly noticed that on a number of occasions, we retraced our steps. Well, if Jaxxon were on the level, I couldn’t blame him for being paranoid. However, I was surprised that he didn’t seem to realize that it was all in vain. I had known that Cu’enmerengi didn’t share the sensory acuity of the Cu’enashti; it was then I realized that they didn’t even have the means to conceive of it.

It struck me how different we were. Cu’enashti, Cu’enmerengi and Cu’ensali called ourselves subspecies of Cu’endhari. We’d assumed that was true because we all emanated from the same species of nau’gsh, Pseudonau’gshtium somniare. What if we were three entirely different forms of life which happened to take form in the same species of nau’gsh? We might have made some fallacious, even potentially dangerous assumptions.

Our own origins were slightly different from the rest of our people. As far as I knew, all the other Cu’endhari descended from an intermediate subspecies known only as Squirrel Trees. Those trees, in turn, descended from a nectarine planted by the explorer Ernst Sider centuries before Dolparessa was colonized, a seed which had mutated upon contact with an energy leak from the nul-universe. On the other hand, the Ashtara grove was the direct descendant of that nectarine, the Father Tree, Ariel. These were truths we had learned through Tara’s visions and her careful botanical research. They were truths unequivocally rejected by the Convocation of the Forest. Compared to the massive Cu’enashti nau’gsh, the nectarine was little more than a fruit-bearing shrub. No one wanted to admit that something like that was an ancestor.

Such were my thoughts as we traversed the tunnels. Finally, at the end of a passage we had travelled twice before, Jaxxon paused. He pulled a card from a concealed pocket in his vest and waved it in front of the wall. Examining it closely, I could see that it was makeshift, a slip of synthboard with a tiny identachip tacked to it. Very paranoid – usually access codes were available through our datapads. But then again, high security was usually achieved through retinal or genetic scanning. Why use something which could be lost or stolen?

A door slid open – a door very cleverly concealed to be invisible to a casual glance. He signaled for me to enter.

I was shocked although not at the presence of the door. I had noticed the door earlier, had noted it as being quite peculiar, since there was nothing behind it. But there was something behind it – a small chamber. I couldn’t understand how I had missed something that glaringly obvious. Then this was where the conspirators had met, and they had some way of concealing it from me. Perhaps they weren’t as obtuse as I had thought.

Curious, I entered. The door slid shut behind me.

The room was entirely barren; even the door had vanished. I felt as though a switch had been flipped, leaving me in complete darkness. It wasn’t a matter of physical light, of photons, it was a matter of connectivity. I couldn’t sense Atlas, nor any of the trees in the grove. I couldn’t sense Tara.

I couldn’t sense Tara. That should have been an enormous source of distress. Without her as a focal point, I and I was incapable of functioning. I should’ve been overwhelmed with enormous amounts of sensory data, a situation which would threaten my sanity within hours. The only remedy for this condition was to bury myself in memories of her, bury myself deep in the branches. Unfortunately, I couldn’t sense the branches, either.

There was no need. I recalled a human creation called a “sensory deprivation chamber.” I had never been able to grasp the concept before, but it must be similar. I could sense nothing, nothing at all. The source of infinite distraction was gone, and for the first time in my existence, I could think clearly without using Tara as a reference point.

I was alone.

“Jaxxon?” I tapped at the space where I supposed the door to be. I received no answer. I hadn’t really expected one. I was intelligent enough to realize that I had been tricked.

The entire room seemed lined in metal. Upon a more careful examination, I could sense that there was an opening of a few molecules breadth around the door – sealed quite well, but on an atomic level, everything is far more empty than solid. The gap was enough to let my human body have some access to the sensorium of our trees, but not tap into their power. I still felt nothing from the branches. I still couldn’t feel Tara.

I ran my fingers across the wall, but I couldn’t analyze its chemical composition. At first, I thought it was part of the blackout effect, but then I realized that I had no trouble analyzing the air. There was something strange about the metal, something blocking my abilities. Also, there was something very familiar about the way it felt. I tried to remember.

I had no branches. I couldn’t remember anything.

Not anything? Not even Tara? I tried to picture her face. It was so foggy, a vague visual impression in stark contrast to the precision of branch memory. I, who knew by instinct the composition of her sweat, could barely remember touching her skin, a feeling like my hands were made of plastic.

How in hell did humans ever manage to think anything with these pitifully inefficient brains? How did they ever manage to engineer interstellar travel? It would’ve been like using a butter knife to chisel Michelangelo’s David.

I forced myself to think. My situation was intentional and carefully planned. Someone wanted me captive, but why? Was I a hostage? Or was I simply being detained to keep me from interfering with the actions of the rebels?

The space around the door wasn’t enough to accomplish much. If I focused incredibly hard, I could sense the grove, but couldn’t draw energy in any quantity from any of the trees. The bark had gone cold. Cut off from the mothman, the branches had probably gone into stasis the way they do when I and I first indwells in a new tree.

That meant I couldn’t perform alchemy on any significant scale. Even if I could, what would I have to operate on – the molecules of air? Ex nihilo creation was out of the question. And even if I did manage to create something, using up the air would have very unfortunate effects on my human body.

And then I realized that there was a good possibility that this would happen anyway. The room was sealed; there was no ventilation into it, and poor ventilation in the tunnels. Perhaps I wasn’t a prisoner at all. Perhaps this was a death sentence.

The more I thought about it, the more likely it seemed. There was no means of communication into or out of the room. That meant the only way to negotiate would be in person, and opening that door would be dangerous to anyone fool enough to try it. The minute I had contact with the grove, I could obliterate my captors with a thought – and I might be angry enough to do it. It was a risky thing to double-cross God.

Could I use my human frailty to my advantage? If I died, perhaps I and I could use my corpse as fodder for alchemical creation. Right now, He was using a significant part of His energy to animate me. Also, as time passed and I became hungry, thirsty and oxygen deprived, He would expend energy to repair Ailann Tiarnan’s body until He was so depleted that it would be impossible to sustain me. Perhaps the smartest plan was to admit to the inevitable, committing suicide as soon as possible.

It was easy enough to stop my heart from beating. It took almost no effort at all.

I awoke, sprawled on the chilly floor, covered in sweat, gasping for air. A numb agony in my chest was receding.

My human brain had a dreamlike recollection of those few seconds of death – of the mothman flailing to free Himself from the cocoon of my body and failing. There wasn’t enough energy even for that. For the first time, I understood the frustration of those Cu’enashti too weak to change forms at will. The skill had always come to I and I so easily. Atlas was a massive, and thus a powerful, tree.

Those mothmen could only be freed by the destruction of their physical bodies. Usually death was enough of a shock to do it. How much damage, decay, decomposition, would it take to loose the mothman? How much precious energy would be wasted?

Energy had been wasted in reviving me, and in fixing whatever damage had been done to this silly brain. I and I must’ve determined that His best chance was for me to think our way out of this.

How?

Perhaps that was the wrong question. Maybe the best place to start was not to ask how, but why. According to Tara’s vision, the Cu’ensali were behind the Cu’enmerengi malcontents. But why? Why now, after a millennium of co-existence? Did they also believe the propaganda they had spread to the Cu’enmerengi dissidents – that their leaders had lost touch with their roots? Were they really so reactionary as to fear the possibility of a life beyond Dolparessa? It is true that a tree has a unique bond to the mother planet, but…our mother planet was Earth. Under the bark, we were all nectarines, despite that most Cu’endhari stubbornly refused to accept the evidence when it was presented to them clearly.

I understood how Darwin felt.

There was a moment of silence while I waited for the answers. Then I realized that no answer was coming. The voices in my head were silent.

I was alone.

I was used to being alone, or so I thought. I held myself aloof from the others, afraid of abusing my authority. So often I had retreated to my quarters in solitude. But to a Cu’enashti, solitude was a very relative thing. There had never been a moment when I couldn’t hear the hum of their voices, touch the solid memories in their branches with the merest thought. There had never been this black, horrifying silence.

When Owen’s branch had been abducted and forced to grow roots hydroponically, Owen almost went mad from the loneliness.

I made myself control my breath. Hyperventilating in a space of limited oxygen was not wise.

I had to pull myself together. Going mad was not inevitable. Cu’enashti begin life with one emanation. Daniel had managed well enough. The Cantor managed for almost a thousand years before Elma’ashra grew Heavensent.

Heavensent. The name triggered fleeting memories of watching the news footage of the burning tree accompanied by a dull ache in my heart. The last time I had thought of this, the pain was a knife – the anger, the confusion, the smell of burning chemicals on her bark…

Not my memories. Owen and Lugh’s memories, no longer mine.

I needed to stop dwelling on that now. I needed to focus. I needed…a drink.

My hands were covered with sweat. I wondered how much energy it would take to convert it to alcohol.

Pathetic! What I really needed was Tara. If I could only remember…

What Ailann Tiarnan’s brain remembered was loving her miserably for years, all the pointless squabbles, the acid ache of jealousy. I remembered the time I had believed her dead, and how I broke, completely unable to function. I had coped, at first, by drinking, and then by becoming Suibhne. But now, I couldn’t do either.

I remembered the look of recognition on her face when she first saw me standing on the strand below the Atlas Tree. I remembered the joy of our wedding night, the times – all too few – that I had made love to her.

All the pain, and all the pleasure, so faint and fading.

So many years I and I had needed her, just to survive. Here, I was finally free of that. But what was the point of survival, if only to be alone?

I no longer needed Tara to survive, but I loved her. By all that was sacred to me, I loved her. But I also realized that I couldn’t survive without my fellow branches. I couldn’t be alone.

If I didn’t think of something fast, my human body would die, and then the mothman would be alone forever, trapped, unable to get out of this chamber because…

Ailann Tiarnan remembered. Ailann Tiarnan remembered the feel of the metal on the walls: it was nul-matter. And then the I which was no longer I and I remembered…

It had been like this at the beginning, the very beginning, long before I and I was tree or man, long before I and I was any I at all. It had been like this, trapped in the rocks of the nul-universe, knowing nothing of existence, of life, of anything but the endless ache not-I hadn’t had the language to call loneliness. The slightest spark that was not-me, singing in unison with the other not-mes: is there not more? Then Atlas had come, a taproot, the living messenger of Tara, bringing life, an escape from the unnamable torment.

I was alone, trapped again with no way out. I was merely I.

I couldn’t stop shaking. The more I tried to calm my gasping breaths, the more panic took hold. I hugged my knees, rocking back and forth, trying to push the tears back. I had to stop myself from clawing at the floor. There was no point in hurting myself, in wasting energy. I had to think clearly, or I would die and never see Tara again.

Ailann Tiarnan would die, but the mothman would live, bound to this rotting body for thousands of years, hundreds of thousands, as His energy slowly dwindled, until He could no longer think a coherent thought, until He was but a mute coagulation of pain, ending as He had begun.

He would die without Tara. And by the time He did, Tara would have long since died, for without Him to preserve her body, she would begin to age.

I’m ashamed to say that I couldn’t stop myself from screaming.

*****

Cillian puts his hand on my shoulder. « Are you all right? »

I nod silently. I don’t say anything, because I want to ask for a drink.

« Writing is harder than it seems, » says Patrick. « Ailann, I think you need a break from this, and it’s just at the right point of the story to try for a dramatic reconstruction. »

« You mean, to make things up? »

« Yes, from what Tara told us later. It’s the best we can do. You were right about what happened to us – the branches were comatose. None of us have any real memories of the events. »

« I don’t know. It doesn’t seem honest. It’s lying. »

« That’s what writers do, Ailann. They tell lies that are true. »

*****

“He said he was going to talk to Mithras,” Tara repeated slowly.

“Yes, well…” Zosim squirmed. He’d known from the minute that he received her message, he was in trouble. Apparently, the Archon had been missing for a few hours – and it was on his watch. Still, the Archon was the Living God of the Domha’vei. He had seemingly limitless power to create anything he wanted. He was impossible to kill. Surely, he’d be all right on his own.

He must’ve had important business. There must’ve been a reason he hadn’t told Her Eminence where he was going. This put Zosim in an awkward position. Whatever he did was sure to be wrong.

But the Matriarch was certainly upset. “And you believed him?” she snapped.

“Well, I mean, he is God…”

“And I’m God’s wife. No wife in her right mind would ever accept a story like that.”

Zosim wasn’t sure he should, either. Some of the emanations of the Living God were a bit…unstable…but Ailann Tiarnan was known for being reliable. He was the rock upon which life in the Domha’vei was founded, and this behavior was very much unlike him. “Perhaps we should send out a search party,” he conceded.

“No, no, not yet.” Tara paced the length of the anteroom. “He’s only been gone for a few hours. It’s unusual, but no reason to panic, especially with everyone’s nerves on edge. It could blow up badly for no good reason. Just stay alert.”

She cut the transmission, and then poured herself a double rhybaa, staring at it for a moment, poking at the ice. She’d been curt with Zosim, but her nerves were frayed. Ailann hadn’t contacted her since the press conference. She knew that if it were up to him, Ashtara’s emanations would be at her side constantly. The only reason Ash would do something like this was if something was wrong – he was probably trying to protect her from something dangerous he had foreseen. It annoyed her. She knew he always had her best interests at heart, but every time something like this happened, he failed to communicate. Whatever it was, she could live with it, as long as she knew what was going on.

At least now she had Canopus. The nau’gsh in the penjing pot was the fifth tree of the grove, a root cutting grown from Atlas that currently had only two branches. Tara went out on the verandah to finish her drink in the company of the little tree.

The first thing she noticed was that Canopus had lost all its leaves. She touched it; it was cold. Then she spotted it: at the juncture of the two trunks, a third branch was starting. Its silvery bark marked with dark, ocular patters stood in stark contrast to the other two sub-trunks. Tara had thought that Quennel’s branch resembled an oak and Ellery’s an alder, but anyone who had even the most cursory knowledge of Terran tree species would recognize this unmistakably as a birch.

Tara ran into the bedroom, grabbing the pack of trading cards. Solomon had told her that when a new emanation was expected, Suibhne made a card for him and placed it at the top of the deck. Tara drew that card, but it was only Mickey. Then, to make certain she’d understood correctly, she flipped the deck over. On the bottom, Manasseh’s card was exposed. She rifled through the whole deck, but there were no new cards.

“Ash grew a new branch, but there’s no new emanation?” she said to herself. It had to be growing in response to a trauma, a severe trauma. Canopus wasn’t warm – that meant it wasn’t drawing nul-energy. This sort of thing had only happened when Ash had cut himself off from the grove to establish a new tree. There were absolutely no plans for another tree – Canopus was supposed to be the last.

Tara retreated to the ipsissimal suite and checked her messages again. Neither Ailann nor Zosim had contacted her. In fact, there was nothing of note.

“All right,” she muttered. “There’s a better way to do this. Hey Marty! You there?”

“YO!”

To an outside observer, it would have seemed as though she were speaking to a disembodied voice. In fact, she was speaking to a member of a species of intelligent subatomic particles. She had counted on Marty being in the vicinity; the Twist were notorious snoops. They were innately omnipresent, unnoticeable and nosy, which is why the entire species had been deputized as a part of the Skarsian intelligence network. In return, Wynne was skewing the probability of their particle decay to near zero.

“Turn it down, Marty,” Tara said, taking a large sip of her drink. “I need to calm my nerves after that.”

“Sorry, sorry. Never could get the hang of these voice synthesizers. What’s up?”

“I’ve got a gut feeling that Ash is in trouble. But he’s only been missing – I don’t even know if I want to call it that – for a few hours. After what happened yesterday, if I call out the dogs, there will be a major panic.”

There was a brief pause. “Oh, I guess you couldn’t see that.”

“What?”

“I did half a rotation. It’s the equivalent of a nod. So anyway, you think this is a job for PLOT-Twist?”

“If anyone can find him, it’s your people, Marty.”

“True. I’ll ask around. Somebody knows someone who knows someone who knows something.”

There was a knock at the door. “That’s my exit,” said Marty. “Ciao, baby.”

It was Lady Lorma, announcing a visitor – Wyrd Elma.

“Elma, are you all right?” Tara asked, offering her a seat. It was a stupidly rhetorical question: Elma looked exhausted and worn. There was something about her which seemed bleakly unfamiliar. It took Tara a moment to place it. Her pupils were normal; she wasn’t on Gyre.

“No, I’m not. It’s damn annoying. Got any puddins?”

Tara put in the order and offered to make Elma a drink. “Why did it have to be Heavensent?” asked Elma. “I actually liked her.”

Tara wordlessly handed Elma the drink. She didn’t know what to say. Would Elma rather have lost the Cantor?

“I know.” Elma shrugged. “It sounds terrible. But when you can see the future as well as I can, it’s better not to get close to anyone. It always ends badly. That’s why I don’t have any friends.”

“I understand,” said Tara. “I don’t have friends either.”

Elma snorted into her julep. “You must be kidding. You’ve got all kinds of friends, of a wide variety of sentient species, even if you don’t count the harem trees. For someone of your standing, you have a remarkably favorable supporter-to-parasite ratio in your entourage.”

“Elma, I know this can’t be easy, whatever you say. I remember what it was like when we thought we’d lost Owen for good.”

Elma shook her head. “For us, it’s easy. It’s just grief. Thing is, I don’t know how to help the Cantor. It’s not something a human can understand. I’m not used to things I can’t understand.”

Tara sat forward abruptly. “Don’t take this wrong,” she began. “It isn’t meant as a way of brushing off your grief. It’s to warn you – there will be another branch, and soon. A trauma of this magnitude will trigger it.”

“Yeah,” said Elma, slouching back on the couch. “I hadn’t thought about it, but of course there will. Wonder what she’ll be like?”

“The branches that were the results of the biggest traumas were Sloane, Whirljack, Cillian, Suibhne, Lugh, Chase and Lorcan. Cüinn and Hurley were the results of an emanation death, but they weren’t particularly traumatic, the way Cu’enashti judge trauma, which isn’t the way humans judge it. I go to Earth to study and Evan is traumatized. Mickey gets shot in the chest by General Panic – he shrugs it off.”

“I have a bad feeling about this one.”

“You’re the High Prophetess. Don’t you know?”

“You know I can’t see unemanated Cu’endhari. It’s going to be a surprise to me. Unless you want to take some blue amrita and tell me.”

“Better stay sober. Ashtara is in big trouble,” said Marty.

“What?” exclaimed Elma, jumping out of her chair. “I thought I was sober until now.”

“It’s Marty,” said Tara. “I knew it! What’s going on?”

“A friend of a friend of a friend told Joey that Ashtara is trapped in some kind of nul-matter room in the sewage tunnel beneath Albion Port-of-Call.”

“A nul-matter room?” said Tara. “That’s impossible. The largest pieces of nul-matter we’ve ever found were the nullets being used by Esau St. John.”

“Someone’s importing it in quantity, I guess.”

“This whole thing just keeps getting weirder. More unpredictable.” Elma scratched her head. “I’m not sure if I like it.”

“What did Ash say?” Tara asked. “Does he want my help?”

“He didn’t say much of anything. He was freaking out too much to notice Joey’s pals.”

“How could someone possibly not notice you?” Elma asked.

“Do you think that every articulate particle in the multiverse lugs around a vocal synthesizer? Thousands of us live under your noses and you never pay any attention to us – or we to you, either.”

“Is Ash safe?” asked Tara.

“There’s nothing physically wrong with him, not yet,” Marty replied. “Sooner or later, he’ll run out of air. Fred wasn’t sure why he was so upset.”

“I think I get it. Canopus is in stasis. In a nul-matter room, he’d be cut off from the grove.”

“Want me to get a message to him?”

“That trap was very well planned,” said Tara. “That means it might not be entirely sprung. Whoever has Ash is probably monitoring very carefully, waiting for us to show up. Let’s move cautiously and have PLOT-Twist scout out the area first.”

“I’m on it,” said Marty. “Or rather, Billy, Letitia and Fred are, once I can shoot off a daton to them.”

*****

About an hour had passed. In the intervening time, I had counted the molecules of oxygen in the room repeatedly. Originally, there were 0.2653 moles of the gas, but at the rate it was dropping, I was not going to survive long.

Why were my captors doing this to me? Why did they hate me so much? As far as my pitiful memory could recall, I had never done anything to harm the Cu’ensali. It was indeed possible that the Cu’enmerengi felt some resentment, or perhaps were just panicked at how rapidly life was changing on Dolparessa. Panic led to bad decisions; this was something I now understood first-hand. However, I just couldn’t believe that the Cu’enmerengi would turn violent without provocation.

I was trying hard to not to think about Tara. This was a violation of every instinct, but the pathetic scraps of human memory were unbearable. It was a worse fate than even the grandfathers and grandmothers of old, the Cu’enashti whose Chosen had died while we were still oppressed by the Great Silence. At least they could fully immerse themselves in the complete memory of their lost beloved. It seemed likely I would die grasping at tatters.

I wept. It was a luxury I could allow myself, as long as I did not sob. I would die from asphyxiation long before I became dehydrated.

And then – in a scant microsecond, I felt the molecular shift, knew that the door was going to open. There was an instant of blind rage where my innate compassion was vanquished, where it seemed to me that I had become very much the serpent of my tree.

And then – light. Not the light of paltry photons, but the true, pure light of the second sun.

It was Tara, accompanied by half a dozen SSOps agents. “Check for booby traps,” she commanded.

“No need,” I said. “There’s nothing in this room, nothing at all. If there were, I would’ve used alchemy to make an explosive, or a lockpick, or a drill.”

“It’s stuffy in here,” she said, offering her hand to me. “Do you think they were trying to kill you?”

I said nothing. I was afraid my voice would break, and it wouldn’t do for the SSOps troops to see their god weeping hysterically.

Tara grasped my shaking hand. Our eyes met; she understood immediately. “I’ll fucking burn them. I’ll burn every Cu’ensali tree on Dolparessa if I have to.”

“We need to know more,” I said weakly. “We don’t know exactly who was involved…”

Ah, it seemed that compassion had returned. How inconvenient.

“I need a drink,” I said.

*****

Tara commanded the SSOps agents to disassemble the nul-chamber and bring the component materials back to Court Emmere. She reminded them of their oaths of secrecy, which was hopefully unnecessary, but I understood her reasoning. It would be potentially destabilizing to the government if the public learned how easily their Living God had been neutralized.

As we emerged into the light, I could feel my fellow branches waking from their enforced slumber. A part of me wanted to embrace them all, but I held myself away from them. I couldn’t face them, not after what had just happened.

We were able to retreat quietly to the palace without arousing the suspicion of the media. I tended to be an enigmatic figure, and I had not been gone that long, at least from a normal perspective. From my own perspective, I felt a thousand years had passed.

The moment we entered our anteroom, I headed straight for the decanter and downed three tumblers of Scotch in quick succession. I sat numbly on one of Court Emmere’s overly ornate antiquities, staring out the window. I could no longer stop the tears. Tara sat near me, taking my hand. I gripped hers tightly, a bit more tightly than comfortable, and she winced. I was so distraught, I barely noticed, but when I did, it only confirmed my conclusions. “I’m a failure,” I said.

Tara didn’t understand. “Because you couldn’t escape that? It was something none of us could have anticipated. I’d love to know where they got that quantity of nul-matter.”

I felt brittle, as if any word I said could snap me like dry wood, but I had to explain it to her somehow. “I was completely alone, completely helpless. I panicked. But that isn’t the worst part because…”

“Ailann,” said Tara quietly, “you can’t imagine for a moment that I would ever allow something like that to happen to you? I sensed something was wrong and asked Marty. If he couldn’t help, I would have sent out a search party if you weren’t back by nightfall. SSOps isn’t entirely incompetent. They could’ve pulled all the secure cams in the concourse to see where you went. I would’ve had that maintenance level torn apart brick by brick.”

“But I didn’t even think of that,” I said weakly. “Being in that chamber caused me to have a flashback to what it was like in the nul-universe, before I and I existed. I panicked so completely that I forgot my n’aashet n’aaverti. For the first time ever, the mothman lost sight of His vision of your destiny. I’d say that I and I lost sight of it, but He didn’t exist. Atlas – the grove – was gone. There was only I. And I couldn’t see anything, not even that. The thought of being alone – I wanted to die.”

“Ailann,” Tara murmured softly. She stood behind the chair, wrapping her arms around my shoulders from behind. She held me like that for a while, but then I could feel the force within me, descending on blue wings, swooping me up in its expanse and forcing my puppet-body to stand with arms outraised. I was being replaced; I would have to face the music.