Purpose:

To examine the means, methods and tolerances of data collection.

Participants:

Mickey Riley, Marius del Eden’d, Thomas del Eden’d.

Materials:

A crystal ball; datapad access to the imperial archives of Sideria, an infinite supply of puddins.

Hypothesis:

There must be a better way.

Procedure [Reported by Her Eminence Tara del D’myn, Matriarch of Skarsia]:

One morning, I woke in Mickey’s arms. “Time for a workout,” he said.

“I’m surprised. Lately, it’s been Constantine.”

“It’s high time I was redeployed. And after, I have something important to talk to you about.”

After meant, of course, after we fucked in the showers, so I was in a particularly good mood. The High Council had one of its days off, and the populace was extremely happy with the bread and circuses provided by the dedication of the new cathedral.

Mickey made drinks for both of us, then settled in a chair across from me. “You do realize,” he said, “that these so-called experiments have no scientific validity whatsoever. Some of them don’t even make sense. That last one, for instance…”

“I blew it. It was supposed to see whether Callum or Cillian would win the argument, but once I stuck my nose in, it was over. But a lot of these experiments are like that. They don’t measure what they say they’re going to.”

“It isn’t science.”

“I think that, to Ash, it is. Science is methodical, linear and rather plodding. But Ash comes from a universe with bendy bosons. Nothing he does is straight. Nevertheless, it’s effective.”

“You’ll never get this published.”

“I’ve no intention of submitting it to a juried publication. I’m just going to publish it as another set of memoirs.”

“It’s pretty…personal.”

“You should see the fanfic.”

“I mean, the disclosures about our nau’gshtamine levels…”

“Rand’s book includes your cock size in a table in the appendix. There’s no turning back now.”

“But is the data even useful to others?”

“That’s a good question. It’s a common wedding-night tradition to eat the apples of the tree you’ve married. But I’ve never heard of anyone else making the blue amrita, despite the fact that Patrick gave away the secret in his novel, and that was years ago. Certainly, everyone knows how it can be used after I released the book of prophecies.”

“Tarlach says that you have to be a prophet to get the full use of it – and it’s really rare to find a Cu’enashti whose Chosen is a prophet.”

“Why is that, I wonder?”

“It probably has something to do with the fact that the Cantor forbade intermarriage with the descendants of other Cu’enashti.”

“What?” I poked at my ice cube for a few seconds. “No, that makes no sense. How could she forbid the choice? Once a Cu’enashti has emanated, the choice had already been made.”

“Think outside the box. She told the ones with children, and they instilled a taboo in their descendants against going into the forests.”

“Is there any reason why she would do that – other than the fact that it could potentially create a prophet more powerful than Elma?”

Mickey considered. “I can’t think of one. Neither can anyone else.”

“But something slipped up. I got through somehow.”

“I could speculate that it was because you planted Atlas with your own hands. But then again, you didn’t have a family tradition, did you?”

I shook my head.

“We’ve always wondered why you never looked into that.”

“I just have the intuition…there are more than a few skeletons in my family closet. It might be best to leave the bones undisturbed.”

“Well, it bugs me. As the chief of your intelligence agency, I want to know – at least before anyone else does, and can use it against us. Come to think of it, they might have already.”

“Elma knows,” I said. “I’m sure of it. But I’ve never been sure of her. The decisions she makes are so arbitrary. At times, I’ve thought she was working for the benefit of the Matriarchy, at other times, I’ve thought she was working for the benefit of the Cu’endhari. But then again, sometimes it seems like she’s doing it all for her own amusement.”

“Why don’t you ask her?” said Mickey. “I’ll get this investigation started.”

Data:

Predictably, Elma showed up ten minutes later. “Puddins!” she exclaimed.

“I ordered them immediately after Mickey left. I knew you’d want some.”

She took a huge handful. “You’re finally getting the hang of this prophecy business.”

“So what’s the answer? Whose side are you on?”

“I consider myself a warrior for freedom.”

I coughed for several minutes, trying to dislodge the puddin that had become stuck in my throat due to my inordinate laughter.

“I’m fucking serious,” Elma said, pouring herself a drink. “Ever since I started taking Gyre, I could see everything perfectly clearly. And it’s a trap. If you know the future, all you can do is live up to it.”

“It’s only probabilities.”

“Right. It’s only probabilities until you cultivate a tree big enough, powerful enough and smart enough – to grow Wynne.”

She had a point.

“And I’m bored, so fucking bored. I’ll do anything to amuse myself. I told the Cantor that intermarriage was forbidden so there would never be prophets powerful enough to be as bored as I am…until you.”

“Why me?”

“When you were six years old, the 5th Matriarch, may she rot in hell, called for me to take a look at you and Christolea to see if either one of you would overthrow her. I couldn’t lie, so I just gave everyone enough truth to allow them to reach the wrong conclusions. The whole truth was that I could see up until the moment Ashtara became Archon. I couldn’t see past that – at least, not into his future. I could see things around the periphery, things that happened to other people, so I could make some deductions. But Ashtara – the most accurate way of putting it is that he casts a shadow I can’t see through. Still, I wasn’t sure of him until Goliath happened. I had a few things hidden under the bed in case it was necessary to destroy him. But when Ashtara fooled himself into leaving you alone for two years, then I knew that he was a warrior for freedom, too. He had every motivation to want you to march nicely along on the path to your destiny, but it didn’t mean anything to him if you couldn’t choose.”

“Why are you telling me this now – wait. It’s because I never asked.”

“You are getting good.”

“All right, how about I ask this: how far can I trust you?”

“Quite far, I’d suppose. Ashtara is many things, but boring is not one of them. The universe that he would create is full of whimsy, absurdity, and poignant intensity. It’s because he’s eternally in love, and he sees everything with a lover’s eyes.” Elma looked away, and for once, she looked almost sad. “It’s nice to see – when it happens to somebody else. I’ll never love anyone.”

“Not even Elma’ashra?”

“Least of all, her. Oh, and you should be aware that I’ve always got a backup plan. Remember when Nikolai Farlow plotted to destroy the Atlas Tree? The Cantor was prepared to stop him, in case Ashtara made the wrong decision. But he made the right one – as usual, for all the wrong reasons. The real point was that a universe without him would be a much darker place to live. In that alternate future, you were on a path of fire and blood to become galactic empress. What do you imagine would’ve happened then? You would’ve been a big enough nuisance to call down the judgment of the SongLuminants upon humanity.”

That was a sobering thought. But there was something else I wanted to ask her. “What do you know about my ancestors?”

“Sorry, only one free question per customer.” Elma grabbed another huge handful of puddins as she turned to the door. “Why don’t you buy yourself a crystal ball? Every self-respecting prophet should have one.”

Hmph. Well, it was actually two free questions, if you counted the one I hadn’t actually asked. And I had gotten a significant amount of information, more than I usually got out of her.

And then I started to mull it over. The things Elma said seemed to be random, but they usually weren’t. What would Wynne do under these circumstances?

There was a very expensive meditation store in the aristo shopping concourse. It was called Reflections, and it sold incense and wind-chimes shaped like unicorns and things like that.

All right, I had purchased a wind-chime shaped like a unicorn there once. In any case, they might have a crystal ball. I decided to go on a shopping excursion.

The aristo concourse was a safe place for me to go on my own because it would be gauche for anyone likely to be shopping there to approach me. They would just stare at me and follow from a distance, casually pretending to walk in the same direction.

I found the store easily enough. It had a window full of candles. Candles shaped like midnight blue dodecahedrons and scarlet snub cubes and even a non-photo blue truncated cuboctahedron. There was an information card propped next to the display. It read, “All Blueblack Love meditation candles are prepared under the light of the proper star, and scented with the pure essence of the appropriate botanical oil.”

I almost backed out of there and ran back to the safety of the ipsissimal quarters. Then I thought better of it. I barged into the shop. “I’ll take all of them,” I said.

“I just can’t keep these on the shelves,” said the shopkeeper. “Next week, I’m getting in a shipment of votaries with the Minchiate trumps painted on the glass.” He placed each candle in a silken pouch, then gently settled them into a bag filled with protective hypertissue. “Is there anything else I can get for you?”

“You wouldn’t happen to have a crystal ball?”

He led me to the back of the establishment. The entire rear wall was full of various crystals and scrying mirrors. “There are a number of very lovely pieces, but I have one which you might in particular have an interest in. It’s an antique piece, about five centuries old, belonging to a woman named Melanyeh Hyrendule. She was a festival exchange in House del D’myn, and she was reputed to have the second sight.”

The ball looked quite ordinary – no different from dozens of others on the shelves except that it was six times the price. The shop, however, was reputable. “I trust it comes with a certificate of authenticity?”

I trudged homeward with my heavy packages. This is what I get for running out on my own. If I’d have come with an entourage, I’d have had someone to carry it for me. Of course, this twenty-minute venture would have turned into a five-hour expedition because the honor guard would’ve done a security check (useless – Eirelantra is perfectly secure, thanks to Mickey) and all the ladies-in-waiting would have had to have changed into this season’s livery and then fretted about bags and shoes to match.

I decided to stop at an NBAI franchise and get a cup of javajuice and a chocumber profiterole. Sitting on the concourse was interesting. My experience of resurrection at Nightside had left me with slightly enhanced senses, meaning that I could overhear conversations from a distance impossible for a normal human. It was an occasionally useful skill. Today I compiled a complete roster of who was cheating on whom, which casinos were likely to be crooked, and that Aurore, one of the most exclusive boutiques, was on the verge of being bought out by the huge luxury conglomerate Aich and Eddy’s. Rather depressing. I remembered shopping in Aurore as a girl – it always had the most unique items. Vintage flapper dresses, Elizabethan lace collars- where could one find things like that elsewhere?

I suppose Quennel could make them.

Three stores down, Lady Augenblick whispered to Madam Seusey-Seusey, “But why would she want those candles? I mean, he’s right there with her.”

“He isn’t now – maybe they’re having problems,” Seusey-Seusey whispered back. “Or maybe she just doesn’t want anyone else to evoke him. I mean, I wouldn’t really want other women meditating on my husband.” The pair broke into conspiratorial giggles.

It probably did look weird. But then again, if these things worked, I could be spared the pain of dragging out a date palm under the light of Castor.

I had no idea, of course, if they worked. When I got home, I unpacked the box. There were dozens of them in eighteen basic varieties. Then I noticed that there were considerably more of some than of others. To wit: there were far fewer of the candles representing branches already emanated. It only made sense: people wanted a known quantity. The emanated branches had sold first.

In fact, there was only one Lammian Honey-colored icosahedron. Tarlach’s show was still popular, even though he hadn’t done a new series in ages.

Which one should I try? Unfortunately, candles representing the emanations I most wanted to see, Wynne and Rand, weren’t included in the set. I could get Rand next week with the votives, though.

My eyes fell on a silver rhombicuboctahedron. It was number ten on the correspondence list. He didn’t even have a name. What would happen if I tried it? Would Canopus grow another branch?

I chickened out. I took up a truncated dodecahedron colored in Mood Indigo. Evoking Thomas should be pretty harmless.

I lit the candle. What now? There was an instruction sheet with the candles. It said, “Focus your mind on pure thoughts, contemplating the peace which the Archon brings to all of our lives.”

I nearly coughed up a lung.

Lady Madonna came into the foyer. “Are you all right?” she asked.

“I’ll be fine. Oh, I have a question for you. Have you ever heard of a Melanyeh Hyrendule? She was supposed to have been a festival exchange in House del D’myn over five hundred years ago.”

Lady Madonna shook her head. “I was your mother’s retainer. I know all of her family secrets. For example, I know where your mother’s half of the blood of the Matriarch came from. It came from Wild Phil von H’sslr. Wild Phil was quite the ladies’ man, and he couldn’t keep away from the wenches. He seduced your great-grandmother and left her with nothing more than a monthly stipend for the child. Your grandmother had quite a buzzibei in her hatrack about it, and so she did a bit of research on her absent father. Apparently he had connections way back when to the same house as Christolea’s mother. On a hunch, she had herself tested, and it turned out she had the right genetic marker. When she found out she’d passed it to your mother, she invested all of her spare income in having her child combat-trained. She figured that if her daughter had the blood, she was a contender, but the only way a commoner could do something about it was by becoming a battlequeen. She was a sharp one, your grandmum.”

“Ah. Well, that was interesting, if completely irrelevant. Oh, and one more thing. Does it bother you when I call you Lady Madonna? Should I call you Lady Magdelaine?”

Her eyes narrowed. “A bit late for that now, isn’t it, missy? You are getting soft as you get older.”

Shortly after she left, Thomas walked in. “It was the strangest thing,” he said. “Mickey had the feeling that he was being followed, so he ducked down an alley and suddenly, I was emanated. I just went into a bar. I figured that the shadow would never be able to pick me out of the dozens of guys in there.”

Blue-suede shoes and a piebald bowling shirt are unlikely to attract attention on Eirelantra, I thought skeptically. But then again, the spy would be looking for Mickey. “Interesting. But why would Mickey be followed?”

“I dunno. He turned up something pretty interesting, though. The sapline is traced from this ancestor.” He placed a datapad on the table, waving his hand over it; a holographic image appeared. “Her name is Stanislava del D’myn. She got left in the entry hall of Court Emmere in a basket.”

“What?”

“Yeah, they had her gene-tested, but they knew what it was all about. Apparently, one of your ancestors got involved with a village girl.”

“That seems to be a common theme today.”

“She dumped the kid on him. And here’s why: look at the eyes.”

I looked. “They’re green. Cu’enmerengi green.”

Thomas nodded. “Cu’enmerengi can’t stand getting tied down with kids. But as it turns out, your ancestor didn’t have any other kids, and so Stanislava inherited the title.”

“So my powers of prophecy come from a flighty Cu’enmerengi. Big deal. I don’t see why anyone should follow you. It’s not like it makes my line illegitimate. A noble can recognize a child born out-of-wedlock – or a festival exchange, for that matter.” My eyes fell on the candle. “Say Thomas, as long as you’re here…we’ve never actually screwed in the real world.”

He cleared his throat. “Well, I sort of have the all-time record for staying power,” he said. “And my RBI is pathetic. So if I screwed you now, it would lower my average, and only increase my RBI to two. I was kind of hoping that you’d screw me enough times to make it worth my while.”

I looked at him sideways.

He shrugged. “Can’t blame an emanation for trying.”

Later, much later, I decided to look up Melanyeh Hyrendule in the family archive. She had a nest of golden curls, and the bright green eyes that marked her as a Cu’enmerengi. There was something about her defiant glance which reminded me a bit of Claris. I had never thought much of Cu’enmerengi, and it was a little disconcerting to learn that one was my ancestor. But thinking about it, it was better than the other possibility. A liaison with a Cu’enashti before the Great Reveal could have only led to tragedy. The last thing I wanted to learn was that my ancestor was still living as a village grandmother in some port-of-call, eternally pining away for my long dead progenitor.

The story surrounding Melanyeh was strange, though. She had gotten pregnant by Ascar del D’myn, which was taboo: even though the noble houses weren’t at all related to their festival exchanges (whom we now know to be of an entirely different species), they were treated like family. You didn’t boff a festival exchange.

Well, I had considered it with Evan, only briefly. Until I married Ash, and then…

Oh well.

Anyway, I had expected Ascar to be the same man that had fathered the strangely fortunate Stanislava, but the dates didn’t jibe – Stanislava was born over a century later. Her father’s name was Brynnt, and the village girl, Tenniah, looked amazingly like Melanyeh Hyrendule.

I commanded my datapad to take the images of Melanyeh and Tenniah and run a comparison with anyone living in the Capitol Nome over the past five centuries. It was going to take a little time, so I decided to have another go at Thomas.

Results:

Later, much later, I returned to the records, which seemed to indicate a match with a woman named Ventrise Harrigan, a merchant who had had a brief affair with Thensian del D’myn. Thensian happened to be the grandson of Ascar and the grandfather of Brynnt. “She had quite a thing for my male ancestors,” I commented.

“Weird,” said Thomas. “Cu’enmerengi aren’t usually that persistent.”

“This is weird, too. Apparently she got pregnant again. But Thensian was quite broken up by it. He made numerous attempts to find her and the baby, but she disappeared. Things must’ve gotten pretty bad between them to cut out the baby’s father like that.” I retrieved the crystal ball from its stand on the table. It was of exemplary quality – not even a faint dusting of bubbles or a hairline crack marred its clarity. It was as clear as a drop of Gyre. “I never would’ve chosen something like this. I know it’s an enormous rarity, but it looks synthetic.”

Thomas nodded. “Quennel agrees. He likes the little flaws that indicate something is natural or hand-made.”

I gazed into the ball. “There’s something wrong here. Something we don’t know. Melanyeh-Ventrise-Tenniah wasn’t just a pervert or some weird obsessive. The ball belonged to someone of intelligence and focus.” The second trait was unusual in a Cu’enmerengi.

“She’s still alive,” said Thomas. “Of course she is. She lives in Albion Port-of-Call under the name of Aidenne Letreque.”

“I think I fancy a call. It isn’t every day you get to talk to your great-great-great – oh, how many greats would that be?”

“Wait. The name sounded familiar. Jack says he knows her. She was a big hoo-hah in the Cu’endhari arm of PLANT.”

“She was a revolutionary? This gets more and more interesting.”

I sent a message. A few minutes later – the time it takes a signal to transmit from Eirelantra to Dolparessa – she picked up. She looked exactly the same as she did in the holos. Had I expected differently? She was Cu’enmerengi; she wouldn’t age.

She smiled at me; it was an unpleasant, self-satisfied smile. “I always knew that one day you’d call,” she said.

“I have your crystal ball,” I said. “Want it back?”

Suddenly, she looked interested. It was a childlike delight in having found an old toy thought forever lost. “I had to abandon that when I left Ascar. I hadn’t planned it well. I was so certain that it was going to work, and when it didn’t, I had to get the boy out of there fast.”

“And why would that be?”

“I can’t believe you don’t get it, prophet.”

But it was Thomas that answered. “A male couldn’t inherit the right genetic marker for the Blood of the Matriarchs,” he said, “and you didn’t want the chance of incestuously encountering your own descendants when you came back for a second try.”

“Or a third,” she replied. “Third time was the charm.”

“I really don’t get it. Why go through all that trouble to have a baby capable of passing on the Blood of the Matriarchs, and then dump her on a doorstep?”

“I needed for her to exist. I didn’t need to raise her. And for what we had planned, it was better for her to be a member of House del D’myn.”

“And what did you have planned?”

“Why don’t you ask Elma? And send me back my crystal ball, please. It’s the least you can do for your greatest of grandmothers.”

The hologram vanished. “So we’re back at square one,” I said. “It’s almost breakfast time. Let’s order up some puddins.”

Conclusion:

Lady Magdelaine brought up the food from the kitchen. “Puddins for breakfast? I thought I taught you better than that. So I brought something healthier – greengrain broth and turquoise corn toast.”

“The puddins are for me,” said Elma, pushing past her. “I’ve never once put anything healthy into my body.”

“In that case, you’ll want a martini. Martinis all round,” I said to Thomas.

“I’ll pass,” said Lady Magdelaine, exiting.

“Why did you have Mickey followed?” I asked.

“Just curious,” she said. “I was wondering how he’d react when he figured it out. I didn’t think he’d be so paranoid. But then again, he’s the head of SSOps. It’s his job to be paranoid.”

“So why didn’t you tell me this yesterday, and spare me the effort?”

“Aidenne wanted her shewstone back, and I didn’t want to pay for it. Also, you needed the candles.”

“What candles?” Thomas asked.

“So what was the plan?” I pressed.

Elma put on a look of faux-despair. “Really, you haven’t read my collected prophecies?”

“They go back over 900 years. There’s a lot to read.”

“This was a prophecy I made right at the beginning, just after I was forced to work for the 4th Matriarch, may her soul be stewed like a dumpling in boiling Wildebeest consommé.” She picked up the datapad, summoning up the relevant section. It read, “When blood and sap shall mingle, tree over man shall rule.”

“I told the 4th Matriarch that it was meaningless,” said Elma. “I told her that blood and sap had already mingled plenty of times, and that it was talking about the Archon. But I told Melanyeh that it was a messianic prophecy. That a child possessing both the Blood of the Matriarchs and the sap of the Cu’endhari would lead the Nau’gsh to rule over the humans of the Domha’vei. She was a real firebrand, that Melanyeh.”

Elma looked at Thomas while deliberately crunching a puddin. “I didn’t lie to either of them,” she said.

Debriefing:

Mickey: I was really hoping for more sex.

Thomas: I was really hoping for more sex.

Marius: Wait, that was it? I didn’t do a damn thing!

Future Investigation:

A week later, I received a message from Aidenne. At the time I received her signal, the High Council was debating the tax status of the colonies, so I didn’t respond immediately.

The votives had come in that morning. They were veladoras, the wax encased in tall glass containers. Highly convenient, as they could be burned on repeated occasions. I had them delivered to the Ipsissimal Suite – I certainly wasn’t about to carry a set of forty by myself. They came in cartons of ten. There was a note in the box saying that a new product was expected next week – candelabras to hold small glass votives such that the flames would form the geomantic figures.

Unfortunately, the candle I now wanted wasn’t in this set either – I had been worried about Harsh since Beat sent me that note. So instead, I pulled out a candle at random. It was a pale flossflower blue with a screened painting of the Minchiate Trump depicting the zodiacal sign of Taurus on the glass. A real screened painting – not synthesized directly into the glass – no wonder the set had been expensive. I lit the candle; it had a wonderful piney scent.

Marius walked into the room. “This is a surprise.”

But it wasn’t, not really. Mickey had been right – this last so-called experiment wasn’t an experiment at all. Marius was supposed to take part, but did nothing…until I pulled his candle randomly out of the box.

And Aidenne had messaged me. It couldn’t be a coincidence. The experiment hadn’t even started yet.

“I’m going to call Grandmamamamamamamamamamama,” I said, but at that moment, Wyrd Elma barged through the door. Lady Magdelaine trailed after her, looked at me, shrugged.

“Where are the puddins?” the prophet asked. “Tara, you’re slipping.”

“Why are you here?”

“Something is wrong.”

“And…?”

“I’m asking you.”

“You’re the prophet.”

“So are you. And he…” she looked at Marius. “Which one is he? I don’t think we’ve ever met.”

“Marius,” he replied.

“And what do you do, Marius?”

“What do I do?”

“What makes you special in the panoply of sex toys your wife collects?”

Marius was taken aback. “I ski,” he said finally.

“That’s it? Ashtara plans to have 101 of you, and he’s already running low on good ideas.”

“Well I…”

“Why not something more interesting, like a dwarf or clown?”

“I hate clowns,” I said. “They scare me.”

“A mythological creature? Gills?”

“The ability to breathe underwater might be useful,” Marius considered.

“Look, I don’t need a man with a gimmick,” I said.

“The gimmick worked pretty well for Constantine,” said Marius.

“Ash is more subtle than that.”

“Cillian is subtle?” asked Elma. “Suibhne is subtle?”

I decided it was high time to wrest back control of the conversation. “Elma, why the fuck are you here?”

“Um. Let’s see. Oh, because maybe Ashtara told you something. Something that Heavensent wouldn’t tell me. Because sometimes the trees can see things we can’t. Pisses me off in a big way.”

It made perfect sense. As good as we were, Elma and I were only borrowing the time-perceptions of the Cu’enashti. Behind Heavensent was also a mothman – well, maybe a mothwoman. Person of moth?

“Marius, ask Lens if he sees anything important.”

Marius’ eyes unfocused for a second as he listened. Having experienced the pleroma for myself, I now understood why it was so difficult for the emanation to single out a train of thought. There were potentially dozens of conversations occurring simultaneously.

“He sees fireflies.”

“Fireflies?” said Elma. “I’ve only ever seen fireflies in the ghetto. Can we get some puddins in here?”

Marius looked at me quizzically. “The Extinction Wing of the Matriarchal Zoological Garden,” I explained. “We called it the ghetto because the animals there are basically in exile. We offered to reintroduce them to Earth, but CenGov wouldn’t have it. ‘Why would we do something so expensive and pointless?’ they said.”

“They said that things become extinct for a reason,” Elma added. “Like CenGov. Did you ever see the fireflies?”

I shook my head. “I was too busy looking at the velociraptors. I could understand why they didn’t want to reintroduce them to Earth.”

“Lens says that he didn’t see actual fireflies. He says that he meant that there’s a visual effect that is keeping him from seeing clearly, and it looks like a cloud of fireflies. He can still see your destiny, though. And Till says he wants to go to the zoo.”

“All right,” I decided. “I’m sure that this message from Aidenne is connected. I’m going to try returning her call.”

“Puddins?” asked Elma.

I sent for an order of puddins, an order of scampi-flavored biiskits, and a pitcher of sangria. Then I called Aidenne.

A few moments later, her holographic image appeared. “I had something I wanted to tell you,” she said, “but now I’m not sure I should.”

Marius and Elma exchanged a look which contained an unmistakable comment: Cu’enmerengi.

“Was it important?’ I pressed.

“Probably,” she said. “Probably very important. But I don’t know if I want to get messed up with Ashtara. Whenever his name is mentioned in the Forest, either the word ‘monster’ or the word ‘savior’ inevitably follows.”

“You still haven’t clarified what side you’re on,” I said.

“I’d stay right out of it,” Aidenne replied, “if you weren’t my descendant. I feel as if I owe you something. But come to think of it, it should be the other way round. You should owe me something.”

Marius and Elma exchanged a look which contained an unmistakable comment: gold-digger.

And now I was going to have to play along with it. Whatever she had to say, it had better be worth it. “Come to think of it, you’re my only living relative,” I said sweetly. “That must be worth something. I think I have a few spare estates…”

“I’d think at least a Duchy. Remember, I was a festival exchange back when I was Melanyeh. I have a right to a title.”

“Patrick had to kill the Matriarch’s last only living relative,” said Marius darkly.

“Ashtara is so jealous,” said Elma, laughing. “Of course, my immediate family died centuries ago. I haven’t bothered keeping track of the line.”

“Let’s not bring up Melanyeh,” I said, “since acknowledging her would render the parentage of Stanislava del D’myn incestuous on a technicality. I think we’re better off giving Tenniah the title of Brynnt del D’myn’s official concubine. That will entitle you to a portrait in the Stella Maris Hall of the Imperial Palace at Vuernaco.”

“I rarely go to Sideria,” she said. “It’s too much strain for me to stay for more than a short period of time. And I’d have to have my portrait painted.” But I could see that her resistance was waning. The thought of an official portrait was too appealing to her vanity.

“Driscoll Garret could do it,” I said. “He’s only Dolparessa’s most renowned artist.”

“Driscoll is going to cough up a filthfrog,” muttered Marius under his breath. “He hates commissions.”

“Where are those puddins?” asked Elma. “Are they bringing them by camel?”

“Well, I suppose I have a patriotic duty to tell you. I’m not happy about it though. I could be called a traitor to my species.” She paused dramatically. “Some of my old friends from the radical Cu’enmerengi faction are back in action. They’ve always found it hard to put their trust in Cu’enashti, since they see them as toadies for their human masters.”

Marius was seething, but said nothing.

Aidenne continued. “They were lying low for a while, basically accepting Claris’ argument that things were better for the Cu’endhari now than ever. But as the years passed, they got more and more suspicious of Ashtara. They were actually quite happy when the Cantor kicked him out of the Convocation. They think that trees capable of space travel are abominations – and that includes the K’ntasari. They resisted the K’ntasari inclusion in the Convocation. The thought that Ashtara created them is overwhelming. And his weird grove thing…”

“Don’t talk about me as though I’m not here,” muttered Marius.

“I have to say that I’ve had more than a few second thoughts about my participation in getting him the Archonate.”

“Your what?” Marius sputtered.

“Oh come on. Elma knows. We created the perfect Matriarch – one who had both the sap and the blood. And you just happened to show up and jump our hovertrain.”

“I didn’t want power, Aidenne. All I care about is Tara.”

“I’m not entirely sure anyone believes that…but if they did, it would be enough of a justification to overthrow you. There are plenty of Cu’enmerengi who believe that having a Cu’enashti leader is tantamount to being ruled by humans.”

“And do you believe that?”

“Most of us believe that the Great Reveal set us free. The old ones remember how it used to be. The young ones talk of a Dolparessa ruled by native Dolparessans – that is, Nau’gsh.”

“By native Dolparessan, you must mean the Arya,” I shot back. “The Cu’endhari are immigrants, too.”

“You don’t honestly suppose any sane tree buys that story?”

“It’s the truth,” said Marius. “We’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: I’m not ashamed to admit that my grandfather was a nectarine.”

Elma burst into laughter. “I’m sorry,” she said, “but that’s has to the most ridiculous quote by an intergalactic dictator in all of known history.”

“That ridiculous and insulting claim isn’t helping your case,” said Aidenne. “But the last straw was Heavensent. Not only did she readmit Ashtara, but she travelled to Eirelantra to assume a place on the High Council! Now they’re saying that the Forest is being completely run by an elite of freaks completely divorced from their roots: Ashtara and Elma’ashra and the K’ntasari woman Miranda. And that horrid Philosophia, the so-called wife of the so-called ambassador of the Quicknodes. Even I’m disgusted by that one – a tree married to an AI?”

“I would ask you to not insult my family,” Marius snapped.

“I just find it difficult to believe that Cu’enmerengi could sustain any sort of plot without someone behind them to pull the strings,” said Elma.

“Now who’s being insulting?” asked Aidenne.

“Oh, come on. Without my coaching, you’d have given up after dumping the first failed baby.” She crunched a puddin for emphasis.

“Failed baby,” I murmured. “Whatever happened to those children?”

“Oh, who cares?” said Aidenne, annoyed. “I brought them to Sideria for placement.”

“Come on,” Elma pressed. “Who’s behind the radicals? CenGov?”

“Do you take them for total idiots?” asked Aidenne. “You would’ve seen the plot coming for parsecs if the conspirators were human. Maybe you’ve never noticed, but the second sight doesn’t work on anything made of nul-energy. We’re relying on the extended sensorium of the nau’gsh, and the trees’ perception of nul-energy is different.”

“But…” I began to object. Marius squeezed my knee. I glanced at him, and he gave his head a slight shake.

Wait,” said Elma, “are you saying they’re plotting while in their dryad forms?”

“Then tell me the ringleaders among your people,” I demanded. “Come on, Aidenne, you know how bad this is. It could become a conflict of tree against tree.”

“I’ve said all I’m going to say. I won’t turn against my old comrades, and I don’t know who their leaders are. Consider yourself warned.”

“All right,” said Tara. “Oh, when I get home, Sir Kaman is having a garden party to celebrate our return. I’ll have him send you an invite.”

“She’s lying,” said Elma, when the message had ended. “She knows we can’t see nul-energy, and so she feels free to make up a lie. The mothmen and dryads are transitional forms. They rarely do anything beyond travelling back to the home nau’gsh, let alone form some sort of terrorist cartel.”

“Ash does,” I replied.

“Well, Ashtara is a freak. She was right about that much. Two penises? One is bad enough.”

“I was referring to the several times that Ash has stopped an invasion fleet,” I said coldly. “In any case, both you and Aidenne are wrong. I can see nul-energy quite well in my visions.”

“Oh?” said Elma. “I’m surprised. The amount of surprises I’m having today is leaving me both excited and annoyed.”

“I can see them when I’m using the blue amrita. It allows me to perceive what Ash perceives. Gyre allows you to see what the Arya see…and the Arya don’t have separate nul-energy forms. They only exist as nau’gsh.”

“Huh.” Elma grabbed a big handful of puddins. “Then we better order more of these. It’s going to be a long night.”

“Now wait a minute…”

“We’re looking for something specific. If you just take the amrita on your own, you’re liable to end up in some weird sex fantasy of Ashtara’s. You need someone experienced in prophecy to guide your meditation.”

“I can do it,” said Marius.

“Right. Bjorn the ski instructor. As if you don’t have any ulterior motivations. I know your kind. All you think about is sex.”

“My name is Marius.”

“Ski instructor is the perfect job for a Cu’enashti. ‘Let me help you with your form, my little snow-bunny. Let me massage your cramping thigh.’” She stared at me, waving a puddin in my face. “They’re like dobergators, these trees. You have to let them know who’s boss from the get-go, or they’ll end up running your life.”

“I’m going to order more sangria, too.” I said. “And a chocumber torte.”

“Just hand me the bottle of vodka,” said Marius.

“I wish,” I replied, “but being drunk off my ass isn’t a good idea when I’m going to be buffered out of my mind.”

When our provisions had arrived, I settled onto the couch, placing a drop of the blue liquid on my tongue.

“These damn experiments,” said Marius. “Lately, we’ve gotten no meaningful instructions. It’s like playing a game where no one tells you the rules.”

“Not exactly,” I said. “What it’s like is a rat-maze. We’re trying to figure out which levers give us cheese, and which ones provide an electrical shock.”

“That’s what Gyre is for,” said Elma. “It all comes clear when you change your perspective. It’s easy to get lost in a maze on the ground level. Much easier to solve if you’re looking at it from above.”

“Ash is a creature with wings,” I mused. “Perhaps it’s difficult for him to conceive of how hard it is to solve this maze in two-dimensional space?”

The world turned blue, and Marius was ice-blue. Ice-blue Marius, an ice-blue flame burning with a hundred other candles in the color space. It was by design, a pattern, but one that made no sense to any human. It was a maze looked at from above, but when I was at ground level, all I could see was Marius.

Elma was right. It would only make sense if I changed my perspective. I climbed up on a chair. Not good enough. I boosted myself onto a table, then a display cabinet. Instantly, Marius was beneath me, holding out his arms lest I should fall. “Hey,” he said, “what are you doing?”

His arms looked strong. Ash’s emanations were all very strong, even ones like Daniel, who didn’t appear to be. The strongest didn’t look it at all – like Jamey and Callum. “I’m gonna jump,” I slurred, certain that he would catch me.

“Geez,” said Elma. “When I’m gyring, I won’t put on mascara without wearing safety glasses.”

“You should learn to trust Elma’ashra,” said Marius.

It was less than a second to his waiting arms, but on the trip down I saw it, if only for an instant. I was a drop descending into a lake, forcing ripples outward, ripples which carried reflections of emanations extending from a central pole, a trunk, a tree. That central point was Jack.

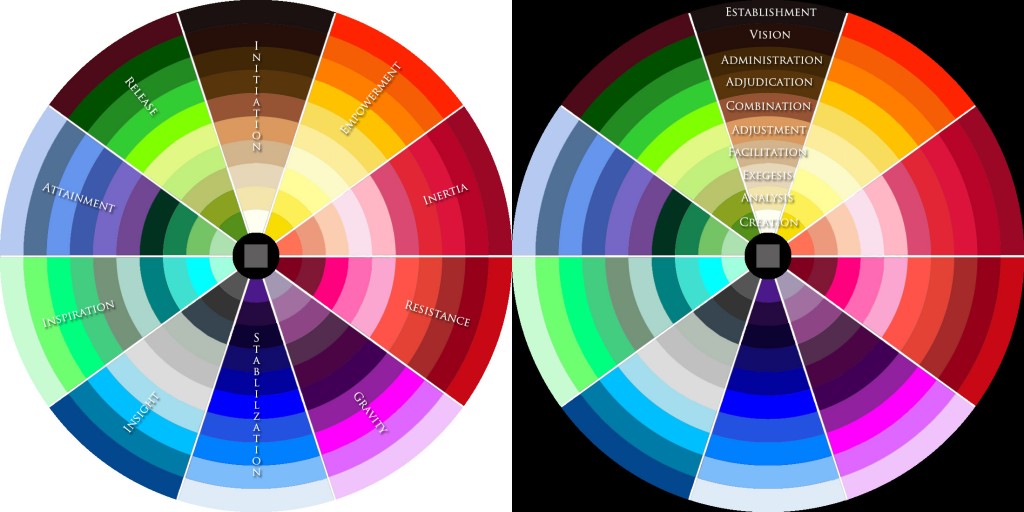

“Malachi was right. The color space is about relationships. But it’s also about function.” I grabbed a datapad. “Here,” I said. “It wouldn’t be science without a pointless chart.”

| Ring Name | Ring Number | Harmonizing Ring | Spoke Name | Spoke Number | Balancing Spoke |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creation | 1 | 10 | Initiation | 1 | 6 |

| Analysis | 2 | 9 | Empowerment | 2 | 7 |

| Exegesis | 3 | 8 | Inertia | 3 | 8 |

| Facilitation | 4 | 7 | Resistance | 4 | 9 |

| Adjustment | 5 | 6 | Gravity | 5 | 10 |

| Combination | 6 | 5 | Stabilization | 6 | 1 |

| Adjudication | 7 | 4 | Insight | 7 | 2 |

| Administration | 8 | 3 | Inspiration | 8 | 3 |

| Vision | 9 | 2 | Attainment | 9 | 4 |

| Establishment | 10 | 1 | Release | 10 | 5 |

“I don’t understand,” said Marius.

“Of course you don’t. Your function is establishing stabilization. If I wanted someone to understand, I’d call Tarlach. His function is analytic empowerment.”

“What does this have to do with the Cu’enmerengi plot?” asked Elma.

I ignored her. “The most important thing, from our point-of-view, is that while we know a number of factors influence nau’gshtamine amide-t production, all other factors being equal, you’ll produce the most nau’gshtamine with someone in either the same or a harmonizing ring, or someone in the same or a balancing spoke. The emanation who is your direct opposite – in both the harmonizing ring and balancing spoke – is a super-producer, and your best choice for a pollen-partner. In your case, of all things, it’s Jamey.”

“Will you get back to business?” Elma demanded. “At least a sex kink would’ve been interesting.”

“This is about business,” said Marius. “Did you notice that all three emanations involved in this experiment are from the outside ring?”

“You’re right. That must be important.”

“It’s bad,” said Marius. “It means you need protection.”

“Tara!” yelled Elma. “Stop with the fucking experiment, and tell me what you see.”

“Fireflies,” I said.

“Fireflies,” muttered Elma.

“Pink fireflies,” I corrected.

“And you’re going to tell us where they fit on the goddamn color wheel, aren’t you?”

“They’re Cu’ensali,” I said.

“What?” Elma and Marius said in unison.

“Cu’ensali,” I confirmed. “That’s why you couldn’t see them.”

“Unlike the two other subspecies, the Cu’ensali spend all their time in their nul-energy forms,” said Marius.

“Now wait a minute,” said Elma. “Cu’ensali have never taken action over anything. They just flit around the forests.”

“Cu’ensali are dumb,” said Marius. “They always ignore the teachings of the Cantor and leave after a few days.”

“That’s like saying that felinoids are dumber than dogs because you can’t train them,” I said. “I’m telling you, I see the Cu’ensali.”

“All right,” said Elma. “And what are they doing?”

“Whispering things to the Cu’enmerengi dissidents. Things that scare the dissidents. Things they try to forget.”

“Just tell us what they fucking said,” snapped Elma. “No need to be so dramatic.”

“Ha! Whenever I ask you something and you’re zotted, you start going on about the peacock moon and the trinity of epsilon.”

“Tara,” said Marius, “what did they say? Listen hard. Remember, Lens can only see them, not hear them.”

“They’ve made a list. The title of the list is ‘Witches.’ The list is Ashtara, Elma’ashra, Ashpremma, Ashkaman, Philosophia, Claris and Miranda.”

“That’s pretty much the Nau’gsh elite Aidenne was talking about,” said Elma. “But why call them witches?”

“You know what you do to witches?” said Marius. “You burn them.”